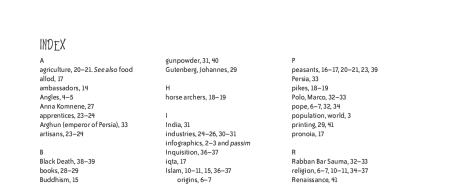

Every good book should have an index. It’s a handy way to find topics, people, and places. We even have one in It’s a Feudal, Feudal World.

The index is such a good idea that you wonder how books ever did without it. So when was the index invented? (And why is this post tagged as being about the middle ages?)

There was a part called the index in many ancient scrolls, but this was a list of topics in the order that they appeared in the book: more like a table of contents than an index of subjects. It was more than a thousand years after them that what we know as the subject index first appeared.

Its immediate parent was a list of words, rather than of ideas: the concordance. The first concordances listed all the places in a book that a particular word appeared. That was very handy for preachers, since they could use the concordance to find bible quotes that used a particular word. The concordance was also useful when interpreting the text, since it listed all the places in the bible a term appeared (in Hebrew, using one place a word appeared to explain the meaning of another place that same word appeared is known as a gezerah shavah).

The first biblical concordances were assembled early in the thirteenth century by the Dominican friars at Saint-Jacques, a community of preachers in Paris. Since every bible was handwritten, each had different page numbers, so the concordances located a word by its book and chapter, plus a letter between A to G to show how far into the chapter it was. (For convenience, the Dominicans marked A to G in the margin of the bible itself.)

From there, it was easy to start making true subject indexes, listing concepts instead of specific words. By 1250 or so, there were indexes for books by Aristotle, Plato, Boethius, and others, many using the A–G marks the Dominicans invented.

In Paris and other major cities, you could get a set of ready-made indexes for these important works: MS lat. 16334 at the National Library of France is a combined index with 570 topics for books by several authors. If you couldn’t get a ready-made index, you could always index the book yourself once you added A–G in the margins. By the start of the fourteenth century, authors wee realizing that an index was useful enough that they should provide one in their book, rather than making the reader buy or create it.

Oddly enough, although France was where indexing was born, modern French books often don’t have an index. Instead, the back of the book has a detailed table of contents, like the ancient index. But indexes thrive in the rest of the world, even if computer keyword searches now give them a run for their money. And we owe them to medieval French preachers who wanted an easier way to look for bible verses.

It’s a Feudal, Feudal World: A Different Medieval History is available for pre-order from Amazon.ca and your local bookstore, to be released in July 2013.